This is the blog section.

Files in these directories will be listed in reverse chronological order.

This is the multi-page printable view of this section. Click here to print.

This is the blog section.

Files in these directories will be listed in reverse chronological order.

When submitting large datasets to the DANDI Archive, it’s crucial to consider data compression options that can substantially reduce file sizes. Smaller files reduce the storage burden on the DANDI Archive and make datasets more convenient to download for users. Neurodata Without Borders (NWB) now supports two file format backends: HDF5 and Zarr. Both formats have built-in capabilities for chunking and compression that can break large datasets into smaller pieces and apply lossless compression to each chunk. This approach reduces file size without altering the dataset values.

DANDI recommends compressing large datasets, but the variety of algorithms and settings available can be overwhelming for NWB users unfamiliar with data engineering. This post aims to answer several common questions:

The answers depend on specific use cases, but our analysis provides general guidelines to help you make informed decisions based on three key metrics: file size, read speed, and write speed. You may also need to consider accessibility - whether the HDF5 or Zarr library can read your file out of the box or requires installation of a dynamic filter.

When considering a compression algorithm, you should consider the following trade-offs:

We conducted an evaluation of several popular compression algorithms in HDF5 using the h5plugin library, which simplifies the installation process for various compression algorithms and makes them available to h5py. For Python users, we highly recommend this package.

For our test data, we used action potential recordings from a Neuropixel probe (SpikeGLX acquisition system) from DANDI:000053, consisting of high-pass voltage data prior to spike-sorting. This represents a common use case for NWB files. While this analysis focuses on HDF5, similar compression principles apply to Zarr backends as well. We relied on h5py to automatically determine chunk shapes, with shuffle turned off.

Before diving into the results, it’s helpful to understand the different compression algorithms tested and how they relate to each other:

gzip: A widely-used compression algorithm based on the DEFLATE method. It’s built directly into HDF5, making it the most accessible option (no additional libraries needed). Gzip prioritizes compression ratio over speed and has been a standard for decades.

zstd (Zstandard): A modern compression algorithm developed by Facebook that offers an excellent balance between compression ratio and speed. It provides adjustable compression levels (higher levels = better compression but slower) and has become increasingly popular for scientific data.

lz4: Designed primarily for speed, LZ4 prioritizes extremely fast compression and decompression at the cost of somewhat lower compression ratios. It’s ideal when read/write performance is the primary concern.

Blosc is not a compression algorithm itself, but rather a meta-compressor that adds additional optimizations on top of existing compression algorithms. Blosc splits data into smaller blocks and applies multi-threading, which can significantly improve performance for large arrays. When you see “blosc” in our results:

The blosc-wrapped versions often show different performance characteristics than their standalone counterparts due to Blosc’s blocking and multi-threading optimizations, which can be particularly effective for numerical arrays like neurophysiology data.

For those interested in learning more about compression principles and their application to scientific data:

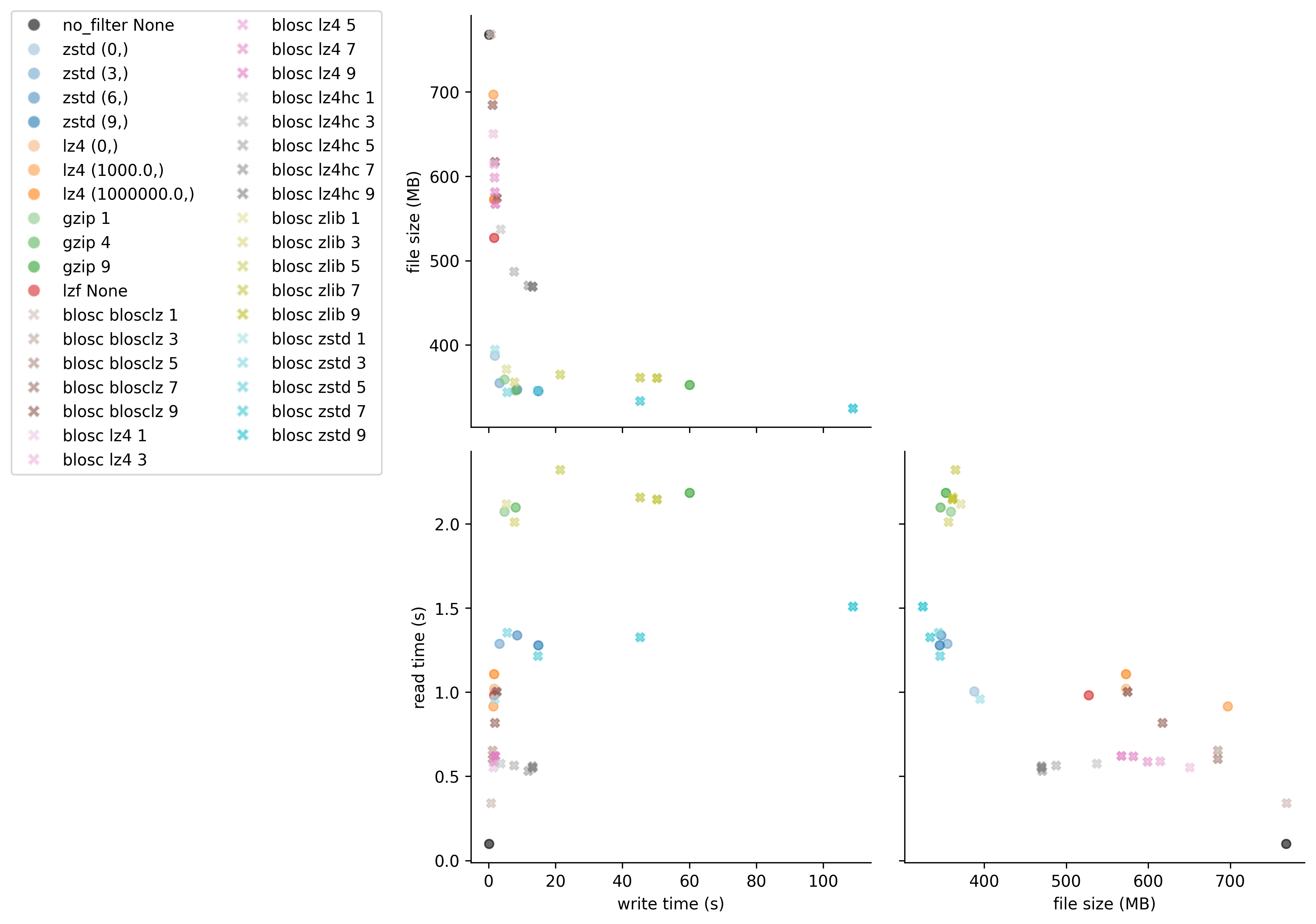

Figure 1: Comparison of compression algorithms. The black circle shows data that is chunked but not compressed. Each color represents a different algorithm, with lightness/darkness indicating compression level.

Figure 1: Comparison of compression algorithms. The black circle shows data that is chunked but not compressed. Each color represents a different algorithm, with lightness/darkness indicating compression level.

Best Overall Performance: zstd level 3

Fastest Read Performance: blosc lz4

Alternative Option: gzip

Best Compression Ratio: blosc zstd

For those interested in the exact benchmark numbers, the table below shows all tested compression configurations with their corresponding write times, file sizes, and read times:

| name | write time (s) | file size (MB) | read time (s) |

|---|---|---|---|

| no_filter None | 0.170 | 768.009 | 0.098 |

| zstd (0,) | 1.857 | 387.450 | 1.005 |

| zstd (3,) | 3.222 | 354.957 | 1.289 |

| zstd (6,) | 8.464 | 347.277 | 1.339 |

| zstd (9,) | 14.810 | 345.556 | 1.278 |

| lz4 (0,) | 1.605 | 572.530 | 1.021 |

| lz4 (1000.0,) | 1.425 | 696.795 | 0.916 |

| lz4 (1000000.0,) | 1.589 | 572.530 | 1.107 |

| gzip 1 | 4.688 | 359.142 | 2.072 |

| gzip 4 | 8.018 | 346.226 | 2.099 |

| gzip 9 | 60.077 | 352.872 | 2.184 |

| lzf None | 1.607 | 527.347 | 0.982 |

| blosc blosclz 1 | 0.650 | 768.438 | 0.341 |

| blosc blosclz 3 | 1.183 | 684.614 | 0.653 |

| blosc blosclz 5 | 1.175 | 684.614 | 0.604 |

| blosc blosclz 7 | 1.846 | 617.389 | 0.819 |

| blosc blosclz 9 | 2.432 | 574.626 | 1.004 |

| blosc lz4 1 | 1.442 | 650.519 | 0.553 |

| blosc lz4 3 | 1.635 | 614.405 | 0.591 |

| blosc lz4 5 | 1.721 | 598.747 | 0.589 |

| blosc lz4 7 | 1.839 | 581.546 | 0.619 |

| blosc lz4 9 | 1.959 | 567.020 | 0.621 |

| blosc lz4hc 1 | 3.612 | 536.971 | 0.576 |

| blosc lz4hc 3 | 7.567 | 487.303 | 0.565 |

| blosc lz4hc 5 | 11.790 | 470.780 | 0.533 |

| blosc lz4hc 7 | 13.138 | 469.490 | 0.560 |

| blosc lz4hc 9 | 13.091 | 469.482 | 0.552 |

| blosc zlib 1 | 5.289 | 371.400 | 2.118 |

| blosc zlib 3 | 7.699 | 356.136 | 2.012 |

| blosc zlib 5 | 21.409 | 364.851 | 2.321 |

| blosc zlib 7 | 45.256 | 361.311 | 2.158 |

| blosc zlib 9 | 50.259 | 360.995 | 2.147 |

| blosc zstd 1 | 1.839 | 394.557 | 0.960 |

| blosc zstd 3 | 5.508 | 344.206 | 1.355 |

| blosc zstd 5 | 14.713 | 345.752 | 1.215 |

| blosc zstd 7 | 45.198 | 333.719 | 1.328 |

| blosc zstd 9 | 108.811 | 324.897 | 1.509 |

By applying appropriate compression settings to your NWB files before uploading to DANDI, you can significantly reduce storage requirements and improve download experiences for users of your datasets. For most neurophysiology datasets using the HDF5 backend, we recommend zstd level 3 or 4 as a good default that balances compression ratio with performance. However, if you have specific requirements for read speed or file size, you might consider blosc lz4 or blosc zstd respectively.

While this analysis focused on HDF5, Zarr offers similar compression options and benefits. Zarr natively supports blosc, zstd, and gzip compression algorithms with comparable performance characteristics. This is an active area of research, and there are newer algorithms that are designed specifically for electrophysiology and available in Zarr. See Compression strategies for large-scale electrophysiology data for a detailed discussion of these algorithms.

Remember that optimal compression settings may vary depending on your specific data characteristics and usage patterns. We encourage you to experiment with different options using the provided code example to find the best configuration for your datasets.

import os

import hdf5plugin

import h5py

import time

from tqdm import tqdm

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

from matplotlib.lines import Line2D

import json

import pandas as pd

import seaborn as sns

# set up parameters for tests

filters = {

'no_filter': dict(

filter_class={'chunks':(10000, 384)},

compression_opts_list=[None],

),

'zstd': dict(

filter_class=hdf5plugin.Zstd(),

compression_opts_list=[

(0,),

(3,),

(6,),

(9,),

],

),

'lz4': dict(

filter_class=hdf5plugin.LZ4(),

compression_opts_list=[

(0,),

(1e3,),

(1e6,),

],

),

'gzip': dict(

filter_class=dict(compression='gzip'),

compression_opts_list=[

1, 4, 9

]

),

'lzf': dict(

filter_class=dict(compression='lzf'),

compression_opts_list=[None,],

)

}

blosc_filters = ["blosclz", "lz4", "lz4hc", "zlib", "zstd"]

results = []

def test_filter(run_name, **kwargs):

"""Get write time, read time, and file size for a run."""

fname = f"{run_name}.h5"

with h5py.File(fname, mode="w") as file:

start = time.time()

file.create_dataset(**kwargs)

write_time = time.time() - start

file_size = os.stat(fname).st_size / 1e6

with h5py.File(fname, mode="r") as file:

start = time.time()

data = file['data'][:]

read_time = time.time() - start

return {

'name': run_name,

'write time (s)': write_time,

'file size (MB)': file_size,

'read time (s)': read_time,

}

def create_mini_palette(color, filter_, compression_opts_list):

"""Create palette of different shades of the same color for a given filter."""

mini_pallete = sns.light_palette(

color=color,

n_colors=len(compression_opts_list)+2)[2:]

for comp_opts, this_color in zip(compression_opts_list, mini_pallete):

palette.update({f"{filter_} {comp_opts}": this_color})

return palette

import lindi

# Load https://api.dandiarchive.org/api/assets/ac23d031-019a-4c07-854d-20a3647f3097/download/

local_cache = lindi.LocalCache()

file = lindi.LindiH5pyFile.from_lindi_file("https://lindi.neurosift.org/dandi/dandisets/000053/assets/ac23d031-019a-4c07-854d-20a3647f3097/nwb.lindi.json", local_cache=local_cache)

data = file['acquisition/ElectricalSeries/data'][:1000000]

print(f"{data.nbytes / 1e9} GB", flush=True)

## run filters

#test non-blosc filters

for filter_name, filter_dict in tqdm(list(filters.items()), desc='non-blosc'):

args = dict(

name="data",

data=data,

**filter_dict["filter_class"]

)

for compression_opts in filter_dict["compression_opts_list"]:

args.update(compression_opts=compression_opts)

run_name = f"{filter_name} {compression_opts}"

results.append(test_filter(run_name, **args))

# test blosc filters

for filter_name in tqdm(blosc_filters, desc='blosc'):

for level in range(1, 10, 2):

args=dict(

name="data",

data=data,

**hdf5plugin.Blosc(cname=filter_name, clevel=level, shuffle=0)

)

run_name = f"blosc {filter_name} {level}"

try:

results.append(test_filter(run_name, **args))

except Exception as e:

print(f"Error occurred for {run_name}: {e}")

df = pd.DataFrame(results)

# Calculate compression ratio (original size / compressed size)

original_size_mb = data.nbytes / 1e6

df['compression ratio'] = original_size_mb / df['file size (MB)']

df.to_parquet("results.parquet")

# uncomment for previous results

# df = pd.read_parquet("results.parquet")

# Save results as HTML table

df.to_html("results.html", index=False, float_format=lambda x: f'{x:.3f}')

# visualization - construct palette

# for non-blosc

counter = 0

base_palette = sns.color_palette(n_colors=11)

palette = {'no_filter None': 'k'}

for filter_, filter_dict in list(filters.items())[1:]:

color = base_palette[counter]

if filter_ not in ('no_filter None',):

palette.update(create_mini_palette(color, filter_, filter_dict["compression_opts_list"]))

counter += 1

# for blosc

for filter_name in blosc_filters:

counter += 1

color = base_palette[counter]

palette.update(create_mini_palette(color, "blosc " + filter_name, range(1, 10, 2)))

n_filters = sum(len(x["compression_opts_list"]) for x in filters.values())

n_blosc_filters = 7*len(blosc_filters)

markers = ['o'] * n_filters + ['x'] * n_blosc_filters

# Create PairGrid without diagonals

g = sns.PairGrid(data=df, hue="name", palette=palette, corner=True, height=4, diag_sharey=False)

# Map scatter plots to lower triangle with custom markers

def scatter_with_markers(x, y, **kwargs):

"""Custom scatter function that uses different markers for blosc vs non-blosc."""

data = kwargs.pop('data')

hue = kwargs.pop('hue', None)

for name in data[hue].unique():

subset = data[data[hue] == name]

marker = 'x' if name.startswith('blosc') else 'o'

color = palette.get(name, 'gray')

plt.scatter(subset[x.name], subset[y.name], marker=marker, c=[color],

s=30, alpha=0.6, label=name)

# Use custom function for lower triangle

for i in range(len(g.axes)):

for j in range(len(g.axes[i])):

if i > j: # Lower triangle only - plot data

ax = g.axes[i, j]

x_var = g.x_vars[j]

y_var = g.y_vars[i]

for name in df['name'].unique():

subset = df[df['name'] == name]

marker = 'X' if name.startswith('blosc') else 'o'

color = palette.get(name, 'gray')

ax.scatter(subset[x_var], subset[y_var], marker=marker, c=[color],

s=30, alpha=0.6, label=name)

ax.set_xlabel(x_var)

ax.set_ylabel(y_var)

elif i == j: # Diagonal - remove these axes

g.axes[i, j].remove()

# Add legend with custom markers

handles = []

labels = []

for name in df['name'].unique():

marker = 'X' if name.startswith('blosc') else 'o'

color = palette.get(name, 'gray')

handles.append(Line2D([0], [0], marker=marker, color='w',

markerfacecolor=color, markersize=8, alpha=0.6))

labels.append(name)

g.fig.legend(handles, labels, loc='center right', bbox_to_anchor=(0, 0.5), ncol=2)

plt.savefig("eval_compressions.pdf", bbox_inches="tight")

plt.savefig("eval_compressions.png", bbox_inches="tight", dpi=300)

In June 2023, Dr. Leslie Claar and colleagues from the Allen Institute published their groundbreaking findings in the journal eLife in the article, “Cortico-thalamo-cortical interactions modulate electrically evoked EEG responses in mice”. Their approach was comprehensive: they stimulated mouse cortex while simultaneously recording with electroencephelography (EEG) and neuropixels probes, comparing brain activity during wakefulness and under isoflurane anesthesia.

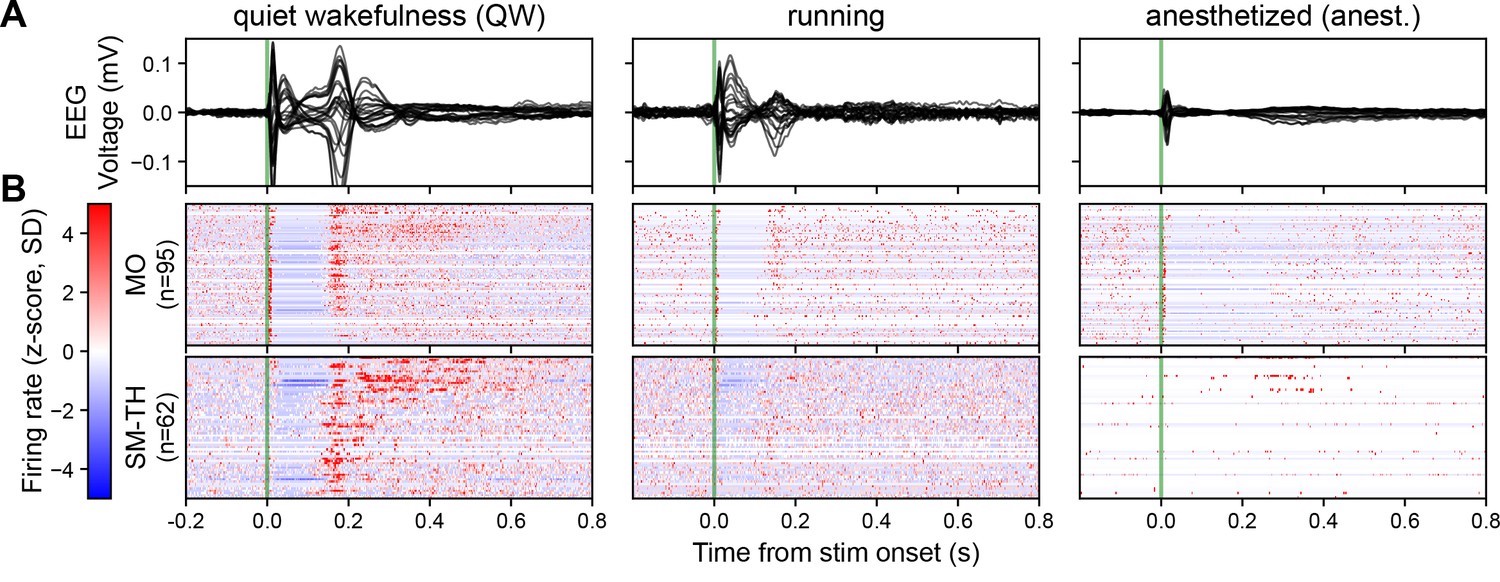

In awake mice, Claar’s team observed a robust event-related potential (ERP) when they delivered pulsatile electrical stimulation to deep layers of the motor cortex (Figure 1A left). This ERP coincided with a distinct pattern of neural spiking, both locally in the motor cortex and in distant sensorimotor-related thalamic nuclei (Figure 1B left). The response followed a three-act play: initial excitation within 25 milliseconds, a period of quiescence for about 125 milliseconds, and finally, a strong rebound excitation before returning to baseline. When the mice were under anesthesia, the story changed dramatically. The ERP’s amplitude and complexity plummeted in response to the same stimulation (Figure 1A right). While the initial excitation persisted in the motor cortex, it vanished in the thalamic nuclei (Figure 1B right). The rebound excitation, along with its corresponding ERP component at around 180 milliseconds, was significantly weakened.

Based on these observations, Claar and colleagues proposed that interactions between the cortex and thalamus are responsible for the rebound excitation phase of the stimulus response. This rebound excitation, in turn, drives the second component of the ERP – a crucial signal of wakefulness.

After their experiments, Claar and her team published their data on DANDI, ensuring that it would remain publicly accessible for any future researchers who wanted to use it. The dataset and manuscript were prepared and published concurrently, which ensured that the dataset included all the paper-relevant data and metadata and curious reviewers could inspect the data directly if they so wished.

Figure 1: Brain state modulates the ERP via cortico-thalamo-cortical interactions. (A) Butterfly plot of ERPs during non-running (quiet wakefulness), running (active wakefulness), and isoflurane-anesthetized states. (B) Normalized firing rate, reported as a z-score of the average, pre-stimulus firing rate, of all RS neurons recorded by the Neuropixels probes targeting the stimulated cortex (MO) and SM-TH. Reproduced from “Cortico-thalamo-cortical interactions modulate electrically evoked EEG responses in mice”.

Just a few months later, in November 2023, Drs. Richard Burman, Paul Brodersen and colleagues at the University of Oxford wrote a paper that included reanalysis of this data. Their findings were published in the journal Neuron with the article, “Active cortical networks promote shunting fast synaptic inhibition in vivo”. They also investigated the effects of anesthesia on brain activity, but narrowed their focus to the differential function of a specific receptor subtype: GABAAR.

Burman and Brodersen’s team used a technique called in vivo gramicidin perforated patch-clamp recording, combined with optogenetic activation of GABAergic synaptic inputs. They compared the GABAA receptor equilibrium potential (EGABAAR) in mice during wakefulness and under urethane anesthesia.

Their findings were striking. In anesthetized mice, GABAA receptor responses were significantly hyperpolarizing, with an average equilibrium potential of -80.8mV. In awake mice, however, these responses could be either hyperpolarizing or depolarizing, averaging at -63.9mV – a state known as the “shunting” regime.

Burman et al. hypothesized that the higher network activity in the awake state leads to a higher concentration of intracellular chloride, which in turn depolarizes the GABAA receptor equilibrium potential. Anesthesia, by broadly suppressing neural activity, indirectly hyperpolarizes EGABAAR. They confirmed this hypothesis by locally injecting an AMPA receptor antagonist (NBQX) which suppressed network activity, and hyperpolarized EGABAAR to -78.0mV.

The Oxford researchers also hypothesized that changes in EGABAAR would lead to changes in network activity, resulting in a bi-directional relationship between the two quantities.

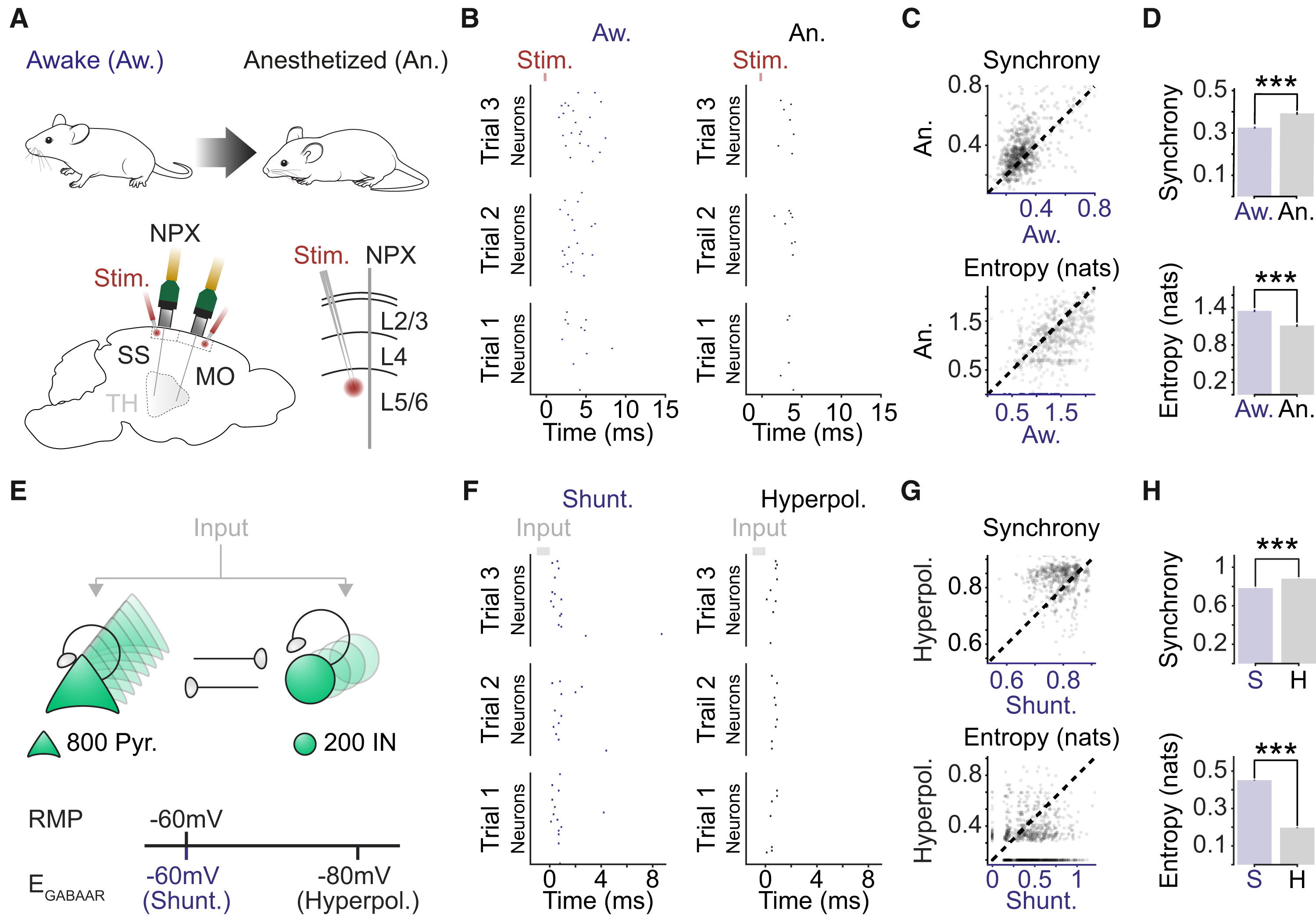

To test this hypothesis, Burman and Brodersen’s team turned to the data from Dandiset #000458 – the very same dataset used by Claar et al. By reanalyzing this data and manipulating a computational network model, they found that setting the EGABAAR parameter to the shunting regime (-60mV) reproduced spiking responses similar to those seen in awake mice (Figure 2 B&F left). Conversely, setting it to the hyperpolarizing regime (-80mV) mimicked the responses seen in anesthetized mice (Figure 2 B&F right). This data provides evidence for the hypothesized bidirectional relationship.

Figure 2: Shunting inhibition promotes local network desynchronization and response flexibility. (A) High-density Neuropixels (NPXs) recordings were used to compare spiking activity in the same cortical neurons under awake and anesthetized conditions. (B) Example raster plots show the spiking activity of a population of neurons in somatosensory cortex (SS). Spiking activity is shown across three stimulation trials for each condition. (C) Neuronal synchrony on a trial-to-trial basis (top) and the entropy of the peri-stimulus histogram (bottom) were calculated for each of the 662 recorded neurons under awake and anesthetized conditions (17 probe recordings in 16 mice). Each dot corresponds to a single neuron and the dashed line indicates the line of equality. (D) Neurons in the awake condition exhibited lower synchrony (top; Aw.: 0.325 ± 0.005 vs. An.: 0.393 ± 0.007, p < 0.001, paired t test) and higher entropy (bottom; Aw.: 1.347 ± 0.018 nats vs. An.: 1.111 ± 0.020 nats, p < 0.001, paired t test). (E) Schematic of network model consisting of interconnected excitatory pyramidal neurons (Pyr.) and inhibitory interneurons (IN). EGABAAR in the pyramidal neurons was adjusted relative to the RMP to create two different conditions: a shunting (Shunt.) and a hyperpolarizing (Hyperpol.) EGABAAR condition. Spiking activity was evoked by delivering brief depolarizing currents (input) of varying amplitudes to each neuron in the network. (F) Raster plots for the same population of pyramidal neurons (n = 50) in the shunting (left) and hyperpolarizing (right) EGABAAR conditions. (G) Synchrony (top) and entropy (bottom) for pyramidal neurons in the shunting and hyperpolarizing EGABAAR conditions (n = 1,000 randomly selected). Dashed line indicates the line of equality. (H) Neurons in the shunting EGABAAR condition exhibited lower synchrony (Shunt: 0.784 ± 0.001 vs. Hyperpol: 0.881 ± 0.001, p < 0.001, paired t test) and higher entropy (Shunt: 0.451 ± 0.002 nats vs. Hyperpol: 0.197 ± 0.002 nats, p < 0.001, paired t test) (n = 16,000 pyramidal neurons from the model). ∗∗∗p < 0.001. MO, motor cortex; Stim., electrical stimulation; TH, thalamus. Reproduced from “Active cortical networks promote shunting fast synaptic inhibition in vivo”.

Together, these two studies provide a rich, multi-level account of what happens to brain activity under anesthesia. They span from macroscale brain signals recorded by EEG all the way down to microscale synaptic responses from a single receptor type. The population spiking data from Dandiset #000458 serves as a crucial bridge between these levels, allowing Burman et al. to explicitly connect their work to the broader field of anesthesia research.

However, it’s important to note some key differences between the two studies. Claar et al. used isoflurane anesthesia and stimulated layers 5/6 of the cortex, while Burman et al. used urethane anesthesia and recorded from layer 2/3. Additionally, while Claar et al. found the most dramatic differences between waking and anesthetized states around 180 ms after stimulation, Burman et al. focused their reanalysis on the initial spiking response within 15 ms of stimulation.

These differences highlight the potential for further reanalysis of Dandiset #000458. Future studies could explore more similar experimental conditions, conduct a more thorough treatment of relevant response time periods, or investigate different aspects of anesthesia’s effects altogether.

For those inspired by the work of Claar, Burman and Brodersen, and their teams, the journey doesn’t end here. We encourage readers from all backgrounds to take advantage of this open science platform by publishing and reanalyzing data on DANDI. We are confident that it will be a smooth and rewarding experience, but don’t just take our word for it – listen to what Dr. Leslie Claar and Dr. Paul Brodersen have to say,

“After organizing our dataset into NWB format, validating and uploading our files was straightforward using a few simple commands from the DANDI Python Client. The tools are well-documented, which made the process of uploading and publishing quite smooth. Within a few months of publishing on DANDI, others were already interested in using our dataset.” – Dr. Leslie Claar

“The DANDI archive is a fantastic resource with great tooling and exhaustive documentation. Its command line interface makes data retrieval and synchronization as simple as possible (but not simpler!). The standardized and well-documented formats for electrophysiological and neuroimaging data ensure that anyone can quickly find their way around a new archive without requiring extensive feedback from the authors that originally collected the data. These features make the DANDI archive a treasure trove of useful and reusable data, unlike the unfortunately still commonplace unstructured data dumps on many other platforms or – worst of all – university servers.” – Dr. Paul Brodersen and Professor Colin Akerman

To get you started on your own reanalysis project, we’ve prepared a Jupyter notebook demonstrating some basic reanalysis of Dandiset #000458. This tool will help you dive right into the data, guiding you through the initial steps of exploration and analysis. We have also prepared a Neurosift walkthrough which demonstrates how to use Neurosift to quickly and easily explore the NWB files in this dataset without even leaving the browser.

By engaging with this open science platform, you become part of a larger community of researchers who are building on each other’s work and driving the field forward. In the world of open science, collaboration and curiosity drive discovery—so why not see where the data takes you?

Date/Time: April 21 - 22, 2022. 9am - 6pm ET

Online: Link will be sent to registered participants.

If you are interested in participating please fill in this form to be sent announcements: Register here

The events will run 9 - 6 ET to accommodate multiple time zones. Participants are welcome to join at any time.

DANDI+Microscopy Starter Kit: We will generate a set Starter Kit that makes it easy for users to navigate these and other Dandisets, including easier visualization of individual files.

Dandiset Abstraction Layer:

Unconference session (11.30 - 12.30 ET)

Visualization/Annotation:

Registration:

Unconference session (11.30 - 12.30 ET)

Please feel free to comment on this community doc.

Neurophysiology experiments often include natural videos (such as behaving animals), which need to be stored with the neurophysiological recordings in order to ensure maximal reusability of the data. These videos are commonly stored with lossy compression (e.g. h264 in an .mp4 file), which allows them to achieve very high compression ratios. It is possible to read these videos frame-by-frame, and store them in HDF5, but since HDF5 is not able to access popular video codecs like h264, the volume of the video in the NWB file is much larger (even when using the available compression algorithms like GZIP). NWB has an option to avoid storing these altogether by linking to these external video files using a relative path to that file on disk. This relative path is stored in the ImageSeries neurodata_type storing it as an attribute of a string dtype. We also need to publish these video linked NWB files in an archive (e.g. in DANDI). For DANDI, which renames and reorganizes the the NWB files, this requires not only uploading the video file on the archive but also changing the path attribute of the ImageSeries to reflect the new file names.

To implement this, we have created a formal naming convention for these video files relative to the NWB files’ path. In addition, these video files are also placed in a specific folder structure relative to the new location of the NWB file during the dandi organize call.

Internally the steps are as follows:

external_file attribute in the NWB files.Note: this solution is specifically for natural videos like those of behaving animals. There are other types of image sequences like image stacks from optical physiology, which do not use codecs like h264; these types of videos can be copied into an HDF5 file.

├── nwbfiles

│ ├── test1_0_0.nwb

│ └── test1_1_1.nwb

└── video_files

├── test1_0.avi

├── test1_1.avi

├── test2_0.avi

└── test2_1.avi

With the path attribute as: image_series.external_files=["../video_files/test1_0.avi", "../video_files/test1_1.avi"]

dandi organizeThe renaming pattern is as follows /<nwbfile_name>/{ImageSeries UUID}_external_file_{number}.mp4.

This UUID is that assigned to the ImageSeries datatype when its created. Thus its possible to lookup a video file linked to an NWB file and vice versa.

└── dandi_organized

├── sub-mouse0

│ ├── sub-mouse0_ses-sessionid0_image

│ │ ├── 933f8cf6-9e4b-405f-8cad-cc031d1fafc9_external_file_0.avi

│ │ └── 933f8cf6-9e4b-405f-8cad-cc031d1fafc9_external_file_1.avi

│ └── sub-mouse0_ses-sessionid0_image.nwb

└── sub-mouse1

├── sub-mouse1_ses-sessionid1_image

│ ├── 03137112-9d42-46b6-9046-45bc9aa7eb5e_external_file_0.avi

│ └── 03137112-9d42-46b6-9046-45bc9aa7eb5e_external_file_1.avi

└── sub-mouse1_ses-sessionid1_image.nwb

With the renamed path attribute as

image_series.external_files=

["sub-mouse0_ses-sessionid0_image/933f8cf6-9e4b-405f-8cad-cc031d1fafc9_external_file_0.avi",

"sub-mouse0_ses-sessionid0_image/933f8cf6-9e4b-405f-8cad-cc031d1fafc9_external_file_1.avi"]

cd dandi_organized

dandi download "https://gui-staging.dandiarchive.org/#/dandiset/101391/draft"

cd dandi_organized

dandi organize -f "copy" --update-external-file-paths --media-files-mode "copy" "/nwbfiles"

–modify-external-file-fields option is a flag.

If active, the organise operation modifies the external_file field of an ImageSeries that holds the local location of an associated video file. It changes the value to the new name as per the convention above.

If no external_file field found in all nwb files, but this option is active, then it logs a warning.

If any NWB file’s ImageSeries has a external_file, but this option is not specified, then it raises a ValueError to avoid breaking the link.

–media-files-mode can be any of copy/move/symlink/hardlink.

This can only be specified if the –modify-external-file-fields flag is True. This is an optional argument, if not specified it defaults to “symlink”: an efficient way to deal with possibly large video files.

dandi validate

dandi upload -i dandi-staging "/dandi_organized"

Example dandiset here

This dataset can then be downloaded using:

mkdir dandi_download

cd dandi_download

dandi download "https://gui-staging.dandiarchive.org/#/dandiset/101391/draft"

The folder will contain all the video files along with the dandi metadata .yml and .nwb files.

Click to view a recording of the workshop

DANDI is a US BRAIN Initiative supported data archive for publishing and sharing neurophysiology data including intracellular and extracellular electrophysiology, optophysiology, and behavioral time-series, and images from immunostaining experiments. For example, data from experimental techniques like patch clamps, silicon probes, and calcium imaging can be published on DANDI. So can data from lightsheet microscopy experiments when combined with associated MRI data.

DANDI allows scientists to publish “dandisets,” collections of data from neuroscience experiments that are often associated with specific papers or projects. DANDI is built to scale with the growing data engineering needs of the community and can easily receive and publish TBs of data for free supported by the AWS public dataset program. It also uses best practices in metadata curation using the DANDI schema and allows users to mint DOIs using Datacite for publishing dandisets.

For neurophysiology data, DANDI supports the Neurodata Without Borders (NWB) standard. The NWB standard ensures that data is shared with the necessary metadata for reanalysis, allows for analyses that aggregate data across dandisets, provides a common platform for building analysis and visualization tools for published data, and allows DANDI to easily extract metadata to provide powerful detailed search features. For MRI and related data, DANDI has been leveraging the BIDS standards and working with other groups to extend support to microscopy and electrophysiology.

With DANDI Hub, DANDI is more than just an archive, but in fact an entire cloud-based collaborative platform, available for free to all DANDI users! DANDI Hub is a JupyterHub with access to high performance multi-core compute nodes and high-bandwidth access to all data hosted on DANDI. DANDI Hub provides many different workflows to interact with your data, including Python, R, and Julia Jupyter notebooks, a terminal, and even a Linux desktop view, all deployed for free and on demand in the cloud. The hub can be used to share code that reproduces key figures from papers, or to interactively explore any dandiset.

You can navigate all data conveniently using the Web app, or for more control we have several software tools for interacting with DANDI. The DANDI Python library and command line interface allows for performant upload, download, and querying. The DANDI REST API can also be used to interface with web applications. Also, all dandisets are made available using Datalad, which provides convenient data access across different systems.

Upload your data today! See our user guide for details. If you have any questions, please use our help desk and we will be happy to assist.